Background on Inclusive Language

There are two prevalent ways that we identify with disability in language: person-first and identity-first. Both options have implications for how we think about disability.

Person-first language distances the person from the disability, ostensibly to separate the person from the negative connotations and stigma with which we have all been socialized. As professionals, many of us have been taught that person-first language is preferable, and some disabled individuals choose to identify as a person first, based on their personal orientation to disability. Example: I am a woman with a disability. I am separate from the stereotypes and stigma you associate with disability.

Identity-first language challenges negative connotations by claiming disability directly. Identity-first language references the variety that exists in how our bodies and brains work with a myriad of conditions that exist, and the role of inaccessible or oppressive systems, structures, or environments in making someone disabled. Example: I am disabled, queer, and Latinx. I have an impairment, and I am disabled by societal barriers.

These language choices underscore the differences between impairment and disability. “Impairment” is the term used by disability studies scholars to refer to a physiological difference in one’s body or brain. Disability is a lived experience with far-reaching political, social, and economic implications.

Retrieved from: https://www.ahead.org/professional-resources/accommodations/statement-on-language

Make Your Language More Inclusive

The terms used for people with disabilities all too frequently perpetuate stereotypes and false ideas. While some words/phrases are commonly used by many, including those with disabilities, usage is likely due to habit rather than intentional meaning. However, conscious thought about what we say, and when we say it, may help to more positively reshape how we communicate about disability in society. The following is intended as suggestion, not censorship, in choosing more appropriate terms.

Less Appropriate: (the) disabled, (the) deaf, (the) blind, (the) mentally retarded

Comment: Terms describe a group only in terms of their disabilities (adjective) and not as people (noun). Humanizing phrases emphasize the person even if the adjective of the disability is included. (The debate over the use of handicap versus disabled has not been settled. Check to see which term individuals might prefer.)

More Appropriate: people with disabilities, deaf people, blind people, persons with a developmental disability

————————————————————————————-

Less Appropriate: deaf and dumb, deaf-mute, dummy

Comment: Terms implies mental incapacitation occurs with hearing loss and/or speech impairment.

More Appropriate: Deaf, Hard-of-Hearing, speech impaired

————————————————————————————-

Less Appropriate: confined to a wheelchair, wheelchair-bound, wheel-chaired

Comment: Terms create a false impression: wheelchairs liberate, not confine or bind; they are mobility tools from which people transfer to sleep, sit in other chairs, drive cars, stand, etc.

More Appropriate: wheelchair user, uses a wheelchair, wheelchair using

————————————————————————————-

Less Appropriate: sightless, blind as a bat, four eyes

Comment: Terms are inaccurate, demeaning. Used as a put-down in most cases.

More Appropriate: blind, legally blind, partially sighted, vision impaired

Less Appropriate: Anita is crippled, – a cripple; That guy’s a crip

Comment: Cripple is an epithet generally offensive to people with physical disabilities (from Old English “to creep”). A second meaning of this adjective is “inferior.”

More Appropriate: Anita has a physical disability; Tom is unable to walk

————————————————————————————-

Less Appropriate: Anita is crippled, – a cripple; That guy’s a crip

Comment: Cripple is an epithet generally offensive to people with physical disabilities (from Old English “to creep”). A second meaning of this adjective is “inferior.”

More Appropriate: Anita has a physical disability; Tom is unable to walk

————————————————————————————-

Less Appropriate: lame, paralytic, gimp, gimpy, withered hand

Comment: Terms are demeaning and outdated.

More Appropriate: walks with a cane, uses crutches, has a disabled/handicapped hand

————————————————————————————-

Less Appropriate: crazy, insane, psycho, nut, maniac, former mental patient

Comment: Terms are outdated and stigmatizing. Not all people who have had a mental or emotional disability have it forever or to the same degree all the time.

More Appropriate: mental disability, behavior disorder, emotional disability, mentally restored

For a more thorough list check out the Disability Language Style Guide

Importance of Inclusive Language Articles

The Importance Of Inclusive Language And Design In Tech

Using inclusive language means avoiding expressions and terms that could be considered sexist, racist, exclusive, or biased in any way against certain groups of people.

Why Disability-Inclusive Language Matters

The current correct term is to use the neutral term ‘people with disability’ – putting the person first.

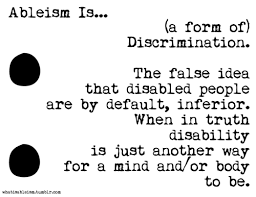

What is Ableism?

For additional information on Inclusive Language please visit the Inclusive Language Guide (PDF).

When writing for any Mason-related communications, please additionally consult Mason’s Editorial Style Guide for other guidelines (requires Mason credentials to access).